The time I went stir-crazy during Covid and reverse-engineered Substack’s private API

Via Stable Diffusion

I try to spend my time on this blog showcasing things I’m proud of - cool side projects, AI tricks, clever reactive programing, that kind of thing.

But I also wanted to once, permanently, write down what happened to my least successful side project. It’s the time I poured hundreds of hours into a terrible app no one used.

It’s time to write about the time I went stir-crazy during COVID and reverse-engineered Substack’s private API.

The setting

I was in a bad headspace in June 2020. I was living across the country from my friends and family in a small one-bedroom apartment. COVID lockdowns were in effect. I’d barely seen anyone in person except my partner for months.

My job was frustrating. I was working as a frontend developer at a local SaaS company that was, well, chaotic. To give a sense of things, our DevOps guy caught a company VIP browsing 4Chan at work. With one year of experience and no computer science degree, I wanted a new job but could not get one.

I couldn’t change my resume, so I fixated on gaining notoriety with a side project. Make something amazing and maybe somebody at a good company would notice and offer a golden ticket out of my dreary day job (this did not work).

The idea

What to make? Well, in another life, I actually worked as a writer and journalist, so I decided to make an app for writers.

At this point, Substack didn’t have any kind of native app. I thought that was strange. Why should Substack writers have to compose newsletters in a web app, even on an iPad? Also, why should they have to use a simple rich text web editor? Why not let them write in Markdown?

Thus, Compose for Substack was born.

The app

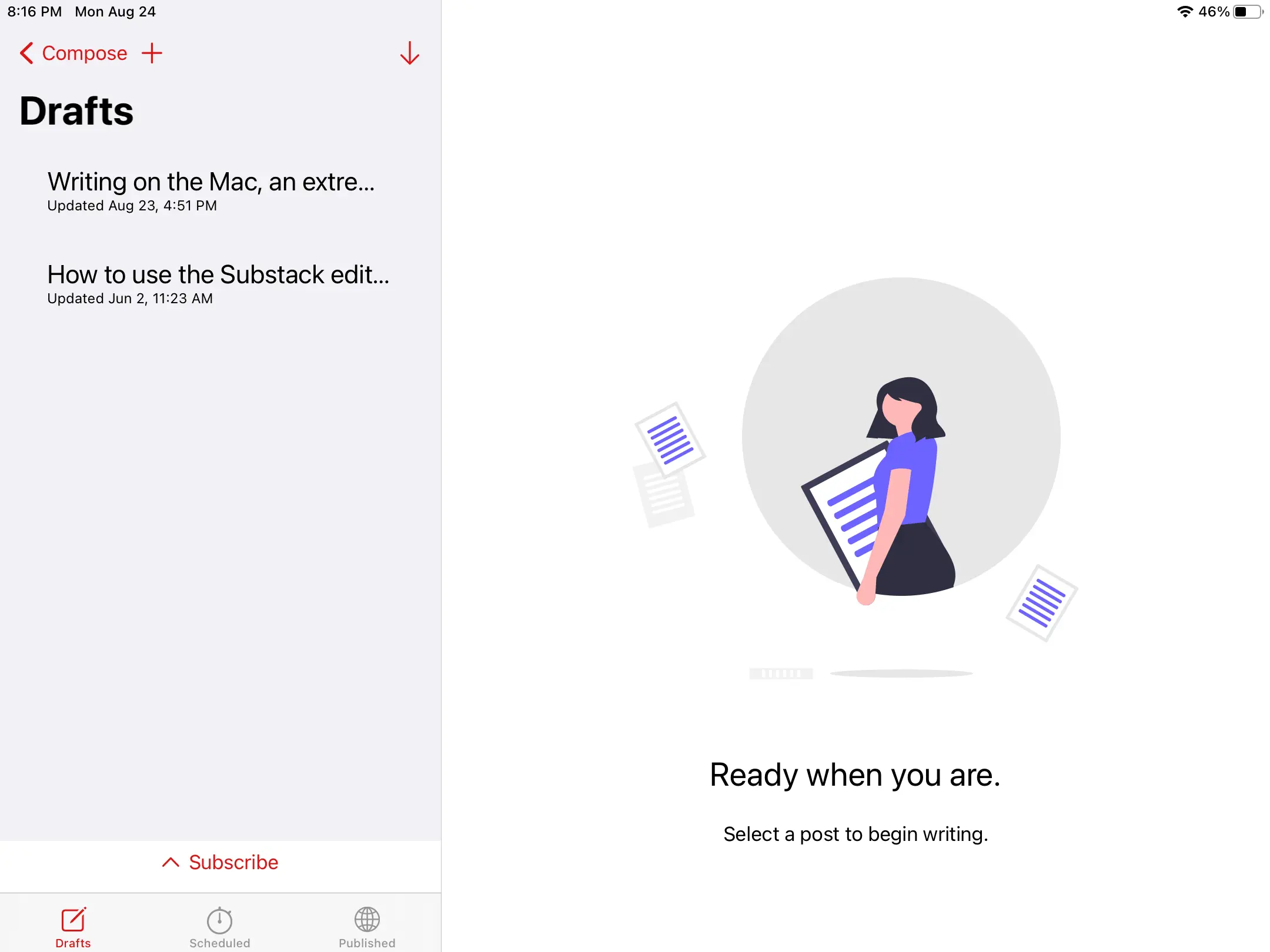

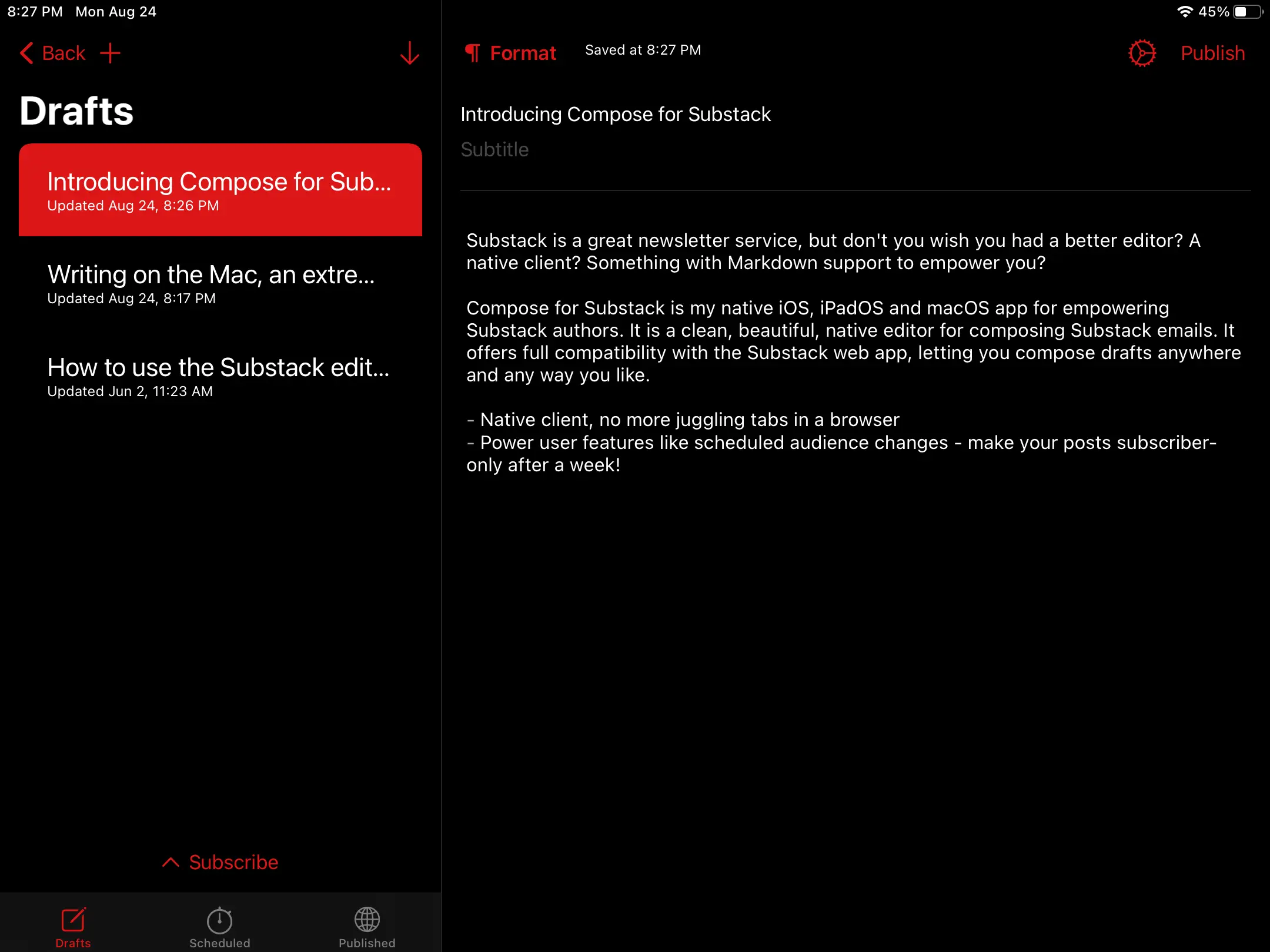

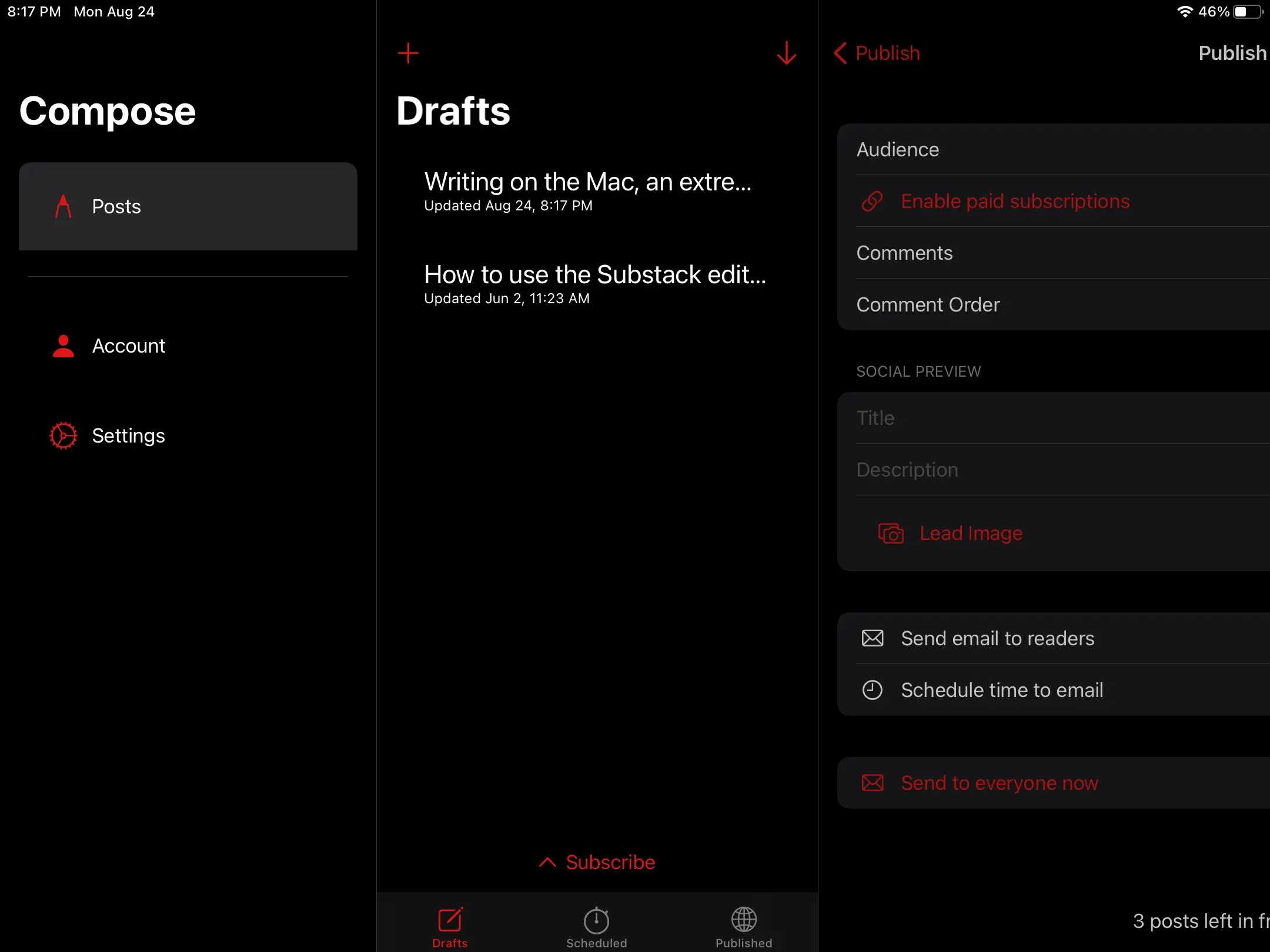

It would be a native iOS, iPadOS and macOS app for newsletter authors. You’d compose Substack newsletter drafts using Markdown, then save and publish, all from a well-designed, native interface.

I didn’t have any iOS or macOS development experience, but Apple had just announced version 2 of SwiftUI. SwiftUI is their declarative framework for writing apps. It felt similar to React, which I knew somewhat well, and so I decided Compose should be written in SwiftUI. This plan seemed like the best way to create a high-quality, native iOS and macOS interfaces without learning the intricacies of UIKit and AppKit.

If you are an Apple ecosystem developer, you may already see some problems with this idea.

The API

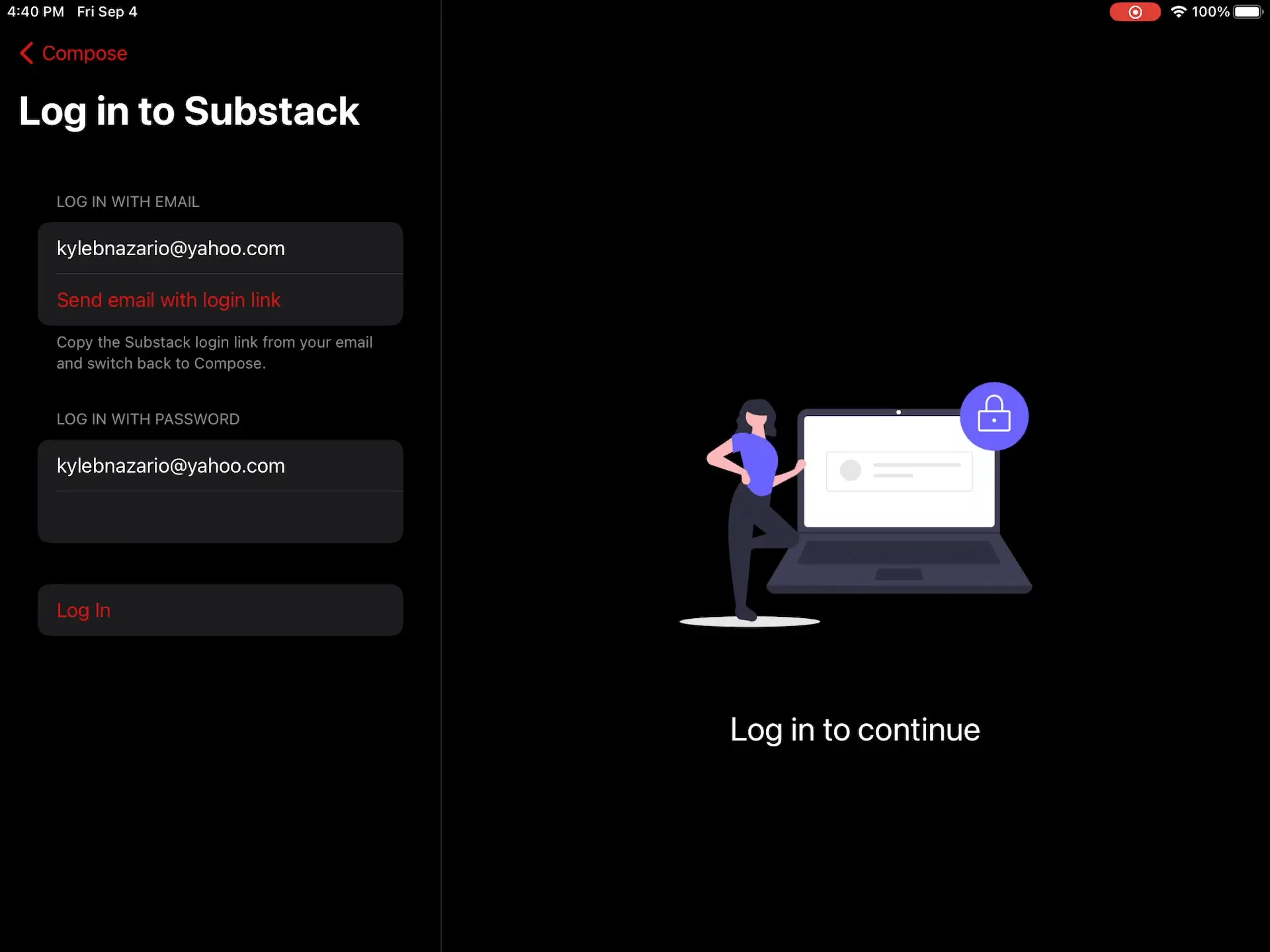

Compose for Substack had an ambitious goal - total interoperability with the Substack web app. My goal was to let the user start a draft in Compose, then view it substack.com and have it be exactly the same.

For this reason, Compose only lightly used CloudKit and Core Data. The most important data, the blog posts, was actually stored on Substack’s servers as a normal draft post - as if the user had written it on substack.com.

This (way too ambitious) goal required reverse-engineering Substack’s private, undocumented drafts API. I played around with the web editor, keeping an eye on the network tab of the Chrome dev tools. I traced every request, building a mental model of how Substack’s frontend communicated with the backend.

I could see why they hadn’t opened it to third-parties. One of the properties on the draft response object actually used the ❤ character as a property key, I think to indicate how many favorites it had.

If you tried to load data for a user’s publication, it just returned a whole kitchen sink. Look at all this.

// SubstackPublication.swift

import Foundation

struct SubstackPublication: Codable {

let id: Int?

let name: String? = nil

let type: String? = nil

let homepageType: String? = nil

let logoURL, logoURLWide: String?

let subdomain: String?

let authorID: Int?

let copyright: String? = nil

let customDomain: String?

let customDomainOptional: Bool? = nil

let emailBannerURL: String? = nil

let emailFrom: String? = nil

let trialEndOverride: String? = nil

let emailFromName: String? = nil

let supportEmail: String? = nil

let firstEnabledPaymentsAt: String? = nil

let heroImage: String? = nil

let heroText: String? = nil

let requireClickthrough: Bool? = nil

let themeVarBackgroundPop: String? = nil

let defaultCoupon: String? = nil

let communityEnabled: Bool? = nil

let themeVarCoverBgColor: String? = nil

let coverPhotoURL: String? = nil

let themeVarColorLinks: Bool? = nil

let defaultGroupCoupon: String? = nil

let paymentsEnabled: Bool? = nil

let createdAt: String? = nil

let podcastEnabled: Bool? = nil

var pageEnabled: Bool? = nil

var applePayDisabled: Bool? = nil

let fbPixelID: Int? = nil

let gaPixelID: Int? = nil

let twitterPixelID: Int? = nil

let podcastTitle: String? = nil

let podcastFeedURL: String? = nil

let hidePodcastFeedLink: Bool? = nil

let paymentsSurveyStatus: Int? = nil

let minimumGroupSize: Int? = nil

let parentPublicationID: Int? = nil

let bylinesEnabled: Bool? = nil

let bylineImagesEnabled: Bool? = nil

let postPreviewLimit: Int? = nil

let defaultWriteCommentPermissions: String?

let defaultPostPublishSendEmail: Bool?

let googleSiteVerificationToken: String? = nil

let pauseState: String? = nil

let language: String? = nil

let paidSubscriptionBenefits: String? = nil

let freeSubscriptionBenefits: String? = nil

let foundingSubscriptionBenefits: String? = nil

let parentAboutPageEnabled: Bool? = nil

let inviteOnly: Bool? = nil

let subscriberInvites: Int? = nil

let defaultCommentSort: String?

let plans: String? = nil

let stripeCountry: String? = nil

let authorName: String? = nil

let authorPhotoURL: String? = nil

let authorBio: String? = nil

let hasChildPublications: Bool? = nil

let hasPublicUsers: Bool? = nil

let hasPosts: Bool? = nil

let hasPodcast: Bool? = nil

let hasSubscriberOnlyPodcast: Bool? = nil

let hasCommunityContent: Bool? = nil

let twitterScreenName: String? = nil

let draftPlans: String? = nil

let baseURL: String?

let hostname: String?

let isOnSubstack: Bool? = nil

let parentPublication: String? = nil

let childPublications: Array<String>? = nil

let siblingPublications: [String]? = nil

enum CodingKeys: String, CodingKey {

case id

case logoURL = "logo_url"

case logoURLWide = "logo_url_wide"

case subdomain

case authorID = "author_id"

case customDomain = "custom_domain"

case coverPhotoURL = "cover_photo_url"

case defaultWriteCommentPermissions = "default_write_comment_permissions"

case defaultPostPublishSendEmail = "default_post_publish_send_email"

case defaultCommentSort = "default_comment_sort"

case baseURL = "base_url"

case hostname

}

}The API wasn’t bad, just messy and not built for outside use. It took a lot of experimentation to decipher which properties to send in PUT requests to save updated newsletter drafts.

One of the hardest parts was reverse-engineering how Substack saved post contents. It looked like they were using Prosemirror and saving the text as one big JSON object. I had to write what was, as far as I knew, the world’s only Swift-language Markdown-Prosemirror converter. I’m proud of that one.

The editor

I also faced the small issue that no one had written an open-source text editor that was exactly what I wanted. Lots of editors had Markdown shortcuts. If you typed **hello**, editors with Markdown shortcuts removed the asterisks and left hello in bold.

I wanted an editor like Byword (which I am using to write this post), which uses Markdown patterns to apply formatting as you type, without removing the formatting characters. If you type **hello** in Byword, it leaves the asterisks and makes the “hello” between them bold.

Nothing fit, so I learned just enough UIKit and AppKit to write a text editor that formats as you type. It took a long time and a lot of effort, and it still slows down if you write too much, but it worked. The editor took Markdown, and, after the user had stopped tpyping for a few seconds, converted it to Prosemirror and synced it to substack.com.

That was about the extend of my SwiftUI success.

The framework

I like SwiftUI. Interfaces are easier to build declaratively, one reason React has taken over frontend web dev. It feels more intuitive than making subclasses and overriding parent functions, like in UIKit.

However.

SwiftUI has enough rough edges, some indie devs have sworn off it entirely. Every year, though, Apple makes it more powerful and less buggy.

In 2020, the rough edges were twice as bad. AppKit-flavored SwiftUI, which of course I picked, is twice that. I picked SwiftUI to avoid learning AppKit and UIKit, but it lacked so much I still ended up learning both.

This was my mistake. To create a high-quality, boutique iOS & Mac app, avoid brand-new frameworks with tons of rough edges. 2020-era SwiftUI was a bad choice for a junior trying to make something nice.

The price

The app would be free to download. You would be able to publish three posts before I’d require a $5 / month subscription.

The subscription was necessary because this app would require ongoing updates to keep it compatible with the Substack API. “Lifetime purchase” was also a bad option, since Substack could cut me off at any time. Better to charge month to month.

I investigated in-app payments. On one hand, RevenueCat seemed like a fast way to get out the door. StoreKit seemed complicated.

I still picked StoreKit. If the app made money, I didn’t want to give RevenueCat a cut. Plus, using a third-party StoreKit library somehow seemed like cheating.

The launch

You are probably starting to sense some red flags. Reader, I sensed none of them.

For example, one small red flag was the audience. At no point during development did I:

- Test the app with Substack writers

- Ask writers if they wanted a native editing app

- Ask writers if they wanted to write in Markdown

- Ask writers if they would pay for an app enabling them to do these things

I plowed on ahead and launched the iOS and iPadOS versions of the app in the fall of 2020.

After several weeks, my total subscribers were…

Zero.

I can’t remember how many people downloaded it, but it wasn’t more than 40. It is the worst-performing side project I’ve ever made.

I was so embarrassed I pulled it off the App Store after just a few weeks. The product-market mismatch was so obvious, more development seemed like a waste.

The lessons

If nothing else, the whole fiasco was a good learning experience.

- Product-market fit is everything. If you don’t have something people will pay for, nothing else matters.

- Technical competence loses to product-market fit every time.

- Get your product in front of users as soon as possible.

- Use proven, established tools you know well so you can build something good quickly.

- Reverse-engineering private APIs is fun but a risky business idea.

- Either build something for yourself, or something you’re extremely confident other people will use.

- Use third-party tools like RevenueCat or Firebase if they help you build faster. It doesn’t matter if they take a bigger cut of your profits. Your top priority is to get out the door and figure out if your app is something people actually want.

The project wasn’t a total loss. I spent some time breaking out my text editor into an open source project, HighlightedTextEditor. It’s been decently successful - 643 stars, with a fair number of issues and PRs on GitHub. I’m glad people are using it, and happy to give back to the iOS dev community.

It’s the least I can do, since I can’t make a good Substack app 😉.